“If you write something and no one reads it, does it exist? Do I exist?”

Izzy – Isabelle Scutley – most definitely exists. She may be invisible to her abusive drunk of a husband, Ferd, who is determined to keep her locked in domesticity in their mobile home in a Louisiana trailer park. But Izzy finds a way out, and the path is paved with words – the poems she commits to paper, first in notebooks, then on rolls of toilet paper, as she crouches in the commode late at night while Ferd sleeps it off.

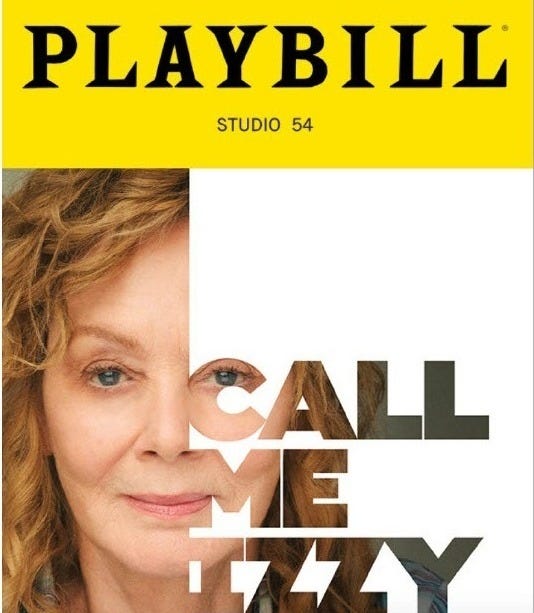

Izzy is brought to vivid life by the formidable Jean Smart in the Broadway play Call Me Izzy, which is running through the end of August. It’s a tour de force for Smart, best known before this for her TV roles in Hacks, Frasier and Designing Women. She commands the stage alone for 90 minutes, inhabiting the personas not only of Izzy, but of Ferd, her neighbor Rosalie, and several other characters.

As a fellow scribbler, I of course immediately identified with Izzy. But I’ve never faced the obstacles that she must overcome; any barriers I’ve had to surmount have been entirely internal. To sit in the darkened theater, watching Izzy wield her eyebrow pencil as a liberating sword, is to witness a testament to the creative spirit and how it can be transformative. Izzy’s poetry provides her with a parallel life, an alter ego, an outlet for the frustrated creative urges that have long resonated within her like the tuning fork of a sensitive musician.

The idea of words as a redeeming force is a powerful notion – in any time, but especially in this moment, when the feral culture warriors of the right are on the muscle, and a government run by a wannabe autocrat is systematically degrading our norms and institutions, our fundamental sense of who we are as a nation and a society.

Language in service of political ideals is often dismissed as “mere words,” empty gestures, a poor substitute for action. But it’s a false dichotomy, because words can lead to action, and can even be a form of action – as Izzy’s narrative arc vividly demonstrates. Her life, her dreams, her raw willpower to transcend her circumstances, all serve as a refutation of the cultural and social forces that would relegate her, and those like her, to the shadows.

I became hooked on books and literature at an early age, giving me printed pathways into an understanding of the often bewildering world around me. One of my most vivid childhood memories is of reading Adventures of Huckleberry Finn together with my father, with him making sure I understood the caustic irony of Twain’s portrayal of enslavement. As a teen, I learned about the Holocaust in Leon Uris’ novels, the rise and fall of Nazism through Upton Sinclair’s quirky, addictive World’s End series (still a guilty pleasure/comfort read!) and American racism in the pages of James Baldwin’s essays and fiction. A bit later, Arthur Koestler’s Darkness at Noon transported me into the heart of Stalinism’s depredations.

The question now is, who is stepping up to the moment? Who are the writers bringing their literary powers to bear on the full-blown crisis that we all face?

Is anyone? New York Times columnist David Brooks recently lamented what he perceives as the decline – or disappearance – of ambitious new novels that seek to capture and define our time. Literature today, he wrote, “plays a much smaller role in our national life, and … this has a dehumanizing effect” on American culture.

“There used to be a sense, inherited from the Romantic era, that novelists and artists served as consciences of the nation, as sages and prophets, who could stand apart and tell us who we are,” Brooks wrote. “As a result of this assumption, novelists were accorded lavish attention as late as the 1980s, and some became astoundingly famous: Gore Vidal, Norman Mailer, Truman Capote.” Today, he wrote, these big-gun novelists and their ambitious works have been supplanted by “Colleen Hoover and fantasy novels and genre fiction.”

I’m not sure I share Brooks’ pessimism, if for no other reason than that fraught moments generate their own cultural imperatives. Great literature doesn’t appear in a vacuum. Mark Twain wrote in an era of resurgent racism. F. Scott Fitzgerald and Sinclair Lewis took on the Ponzi-scheme prosperity and social pomposities of the 1920s. John Steinbeck responded to the desperate plight of those uprooted by the Great Depression. Arthur Miller stared down McCarthyism.

It can take time for writers to catch up with the zeitgeist; Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath was published in 1939, nearly a decade after the onset of the Depression. In the meantime, happily, dramatists are rising to the occasion. George Clooney and Grant Heslov repurposed their 2005 movie Good Night and Good Luck about journalist Edward R. Murrow’s confrontation with Joe McCarthy into a vibrant stage play that leans into the resonances between the Red Scare era and Trumpism. In John Proctor Is the Villain, Kimberly Belflower gives us a very new take on Miller’s witchcraft allegory.

And then we have Izzy, stashing her keeper poems in a Tampax box (because that’s the last place her vindictive husband would ever look) and marking time – until neighbor Rosalie discovers her secret literary life and offers her a new vista.

In the end, we see Izzy alone at a bus stop, with her salvaged writings and sparse belongings, waiting for the headlights of the Trailways coach to illuminate her and her path forward. It’s a modern-day analog to Huck’s gambit, at the end of Twain’s classic, to “light out for the territory.” Like Huck, Izzy is determined to forge her own identity, her own personhood, with her accumulated words providing a resounding affirmative answer to the question she poses at the start. In any era, but perhaps especially in this one, that’s a prize worth grasping, in any way we can.

Ken Fireman is the author of The Unmooring, a historical novel about America in the 1960s. During his work as a journalist, he covered Washington, post-Soviet Russia and other battle zones.

Further reading:

David Brooks, “When Novels Mattered,” The New York Times, July 10, 2025, https://www.nytimes.com/2025/07/10/opinion/literature-books-novelists.html

Glad you exist, Ken.

I second Christine's comment. Terrific piece, Ken. And Demon Copperhead speaks to our times as few recent novels I've read do.